by futurist Richard Worzel, C.F.A.

There is a gigantic pool of highly flammable fuel in the fireplace of our economy, and lots of people are about to start lighting matches. The result may be an inflation conflagration not seen since the 1970s.

In March of last year, I wrote a blog about what might happen next during the pandemic (“The Virus and the Economy”). In that blog, I talked about the velocity of money, which is an arcane economic concept that is rarely discussed, and not widely understood. However, we are getting to a stage where the velocity of money is becoming important – again – so I’m going to take a moment, and repeat the description of what it is, then I’ll talk about why it’s important. If you remember what I said, or happen to understand the velocity of money, you can skip my simplified explanation.

But the bottom line is that the faster people spend money, the more money there is. And people are about to start spending money faster, which can lead to much higher levels of inflation than we’ve see for forty years. That will have consequences.

Here’s what I said in March of 2020:

What Is the Velocity of Money, and Why Should You Care About It?

Let me use a drastically simplified illustration of the economy to focus on the importance of velocity. This example suggests all sorts of other economic concepts, like barter, inflation, hoarding, inventory, spoilage, and so on. I’m going to ignore all of those and focus specifically on velocity.

Imagine that there are only three people in the economy: a farmer who grows grain, a miller who turns grain into flour, and a baker who turns flour into bread. Let’s also imagine that there’s only one piece of currency, a single, silver dollar, and that it’s held by the farmer.

The farmer keeps the silver dollar in a shoebox under his bed, and uses it only once a year, to buy a loaf of bread from the baker in order to celebrate the holidays. When he gives the dollar to the baker, the baker then has enough money to buy flour, which he does immediately, giving the dollar to the miller. The miller uses the dollar to buy grain, which he does immediately, handing the dollar back to the farmer. The farmer gets the dollar back shortly after spending it, but hoards it for the next Christmas. Each person has an annual income of $1/year.

Now suppose the farmer’s wife convinces him to buy a second loaf of bread, this time to celebrate the arrival of Summer. The same transactions occur. And the farmer is so pleased with the result that he buys a third loaf of bread to celebrate the harvest in the Autumn.

Pretty soon he’s buying a loaf of bread every week instead of once a year, with all the other transactions flowing on from that. Now his income is $52/year – and so is everyone else’s. So, their income has multiplied and economic activity has multiplied, even though the amount of hard currency has stayed the same. And it all happens because people are spending money more quickly than they were before.

But now suppose something scares the farmer to the point where he decides he needs to hoard the dollar again, and spend it only once a year. Everyone’s income drops back to $1/year.

The Inflation Spike that Economists Are Already Discussing

That’s what I wrote about the velocity of money 16 months ago. It was important then because people weren’t spending money, which meant that the velocity of money had crashed, and that meant that the economy slowed dramatically. And many people’s incomes crashed along with velocity.

Now the reverse is starting to happen. As people are getting vaccinated, they are starting to go out again, to buy things, go to restaurants, cinemas, plays, and on vacation. As a result, money is circulating much more freely – and quickly. For a time, there will be a spurt of activity, as people rush to eat out and do all the things they have been denied for the past 16 months or so.

And economists are already talking about this surge of activity. They talk about it as a spike – and so it shall be. And that spike of activity is going to bring a spike in inflation. If everyone wants to go out to eat, but many restaurants have closed, or lost suppliers, or can’t yet afford to hire enough staff, demand will outstrip supply for a while, until the initial rush of demand subsides into a more sustainable level of activity, and until supply can build up to meet surging demand.

So, that initial surge of demand is going to outstrip the initial ability of the economy to meet it with supply – and that’s where the spike in inflation is going to come from. Scarce items go up in price.

But that’s not what worries me. That is transitory, and will eventually iron itself out, although it may be many months, or perhaps a couple of years, to do so.

Let’s look beyond that spike. Just suppose that the level of demand returns to where it was before the pandemic. It may actually be lower, or higher, but for discussion’s sake, let’s say it settles out to be the same as it was.

The big economic difference between then and now is that central banks have been pumping out vast amounts of liquidity in a desperate – and largely successful – attempt to keep their economies from crashing. All of that liquidity did not lead to inflation because the money didn’t go anywhere. People were hiding in their homes, not out spending money.

The velocity of money dropped precipitously, and economic demand fell with it.

So, one major difference between the economy now and the economy at the beginning of 2020 is all the liquidity that is lying around in the economy that wasn’t there in early 2020.

Let me use a slightly different analogy. Economic activity is oxygen, which is necessary to get a fire to burn in the fireplace, and warm the economy. When the economy shut down because of the pandemic, the oxygen level dropped. To offset that, the central banks flooded the fireplace with fuel, hoping to get at least some of it to burn, and keep the economy from freezing.

What’s happening now with the increase in economic activity is the oxygen levels are returning to normal…which will make the fuel far more combustible than it has been. The only way to stop all that fuel from bursting into flame and overheating the economy would be to drastically reduce the supply of fuel – being the liquidity in the economy.

The Combustible Economy: This Time It’s Different

So, the result of all that liquidity will be a massive increase in inflation and an overheating of the economy – unless central banks shut off the fuel supply and sop up the excess fuel lying around by slamming on the economic brakes through tightening the money supply – which could cause the economy to hit a brick wall.

Now, despite their attempts to avoid politics, there is no way that central banks want to cause a recession or even a significant slowdown as the economy is just recovering from the pandemic. Elected officials would go ballistic if central bankers tried.

And remember that the Chair of the US Federal Reserve comes up for reappointment – or replacement – in 2022. Hence, the current Fed Chair Jerome Powell knows that he either works to boost economic activity, or he gets tossed out next year.

So, if my concerns are correct, then we may be at the beginning of a new, secular inflation cycle.

If you look at The Economist’s Commodity Price Index, it seems to reflect a major upward shift in commodity prices, which are an early indicator of a broader rise in prices generally. As of June 5th, 2021, their “US Dollar All Commodity Index” had risen by more than 73% in the previous 12 months. Manufacturers and retailers are now responding by passing the costs through to the consumer rather than eating them, as they did over the past year and more.

Anyone Born After 1970 Doesn’t Understand Inflation

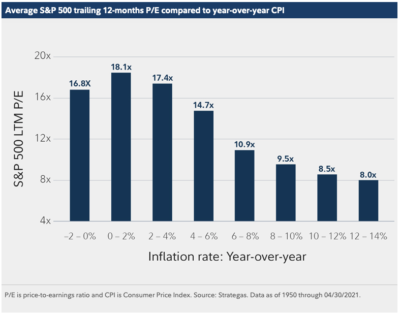

Few economic or financial commentators born after 1970 will have any idea of how difficult or dangerous inflation is. They emerged as adults in a world where inflation always went down, which meant interest rates and mortgage rate always went down, which meant that bond prices and house prices always went up, and stock market price/earnings ratios always expanded, leading to higher stock prices.

As a result, they have an ingrained, gut-level belief that inflation will always be low, with all that that implies. And because of that, they will be caught off-guard if inflation starts a significant, protracted, upward expansion, and they won’t know what to do or how to react.

This will lead to mistakes for policy and corporate governance by all but the oldest decision-makers. And that means that efforts to deal with inflation – in government policy, in corporate decision-making, and in individual consumer decisions – will be misguided, and even potentially disastrous.

It is too early to say the inflation will rage out of control, but it is not too early to consider it as a real threat and take appropriate precautions. And this applies whether you run a business, invest in stocks or bonds, or hold a mortgage on your house. The costs of being wrong – which is my definition of risk – are potentially very high.

And there’s one more aspect of inflation that you need to keep in mind: Inflation robs savers and rewards borrowers. Borrowers take money when it’s valuable, and repay it when it’s cheapened, which transfers value from savers to borrowers. In effect, savers are penalized, and borrowers are rewarded – which is the reverse of what’s been happening for the past 30 years or more.

But that’s only true up to a point. Borrowers have a financial incentive to borrow more and more, because it pays them to do so. Yet, there is a limit, which is when they no longer have enough cash flow to service the debt. Then, suddenly, what was a bonanza becomes bankruptcy as they default on their debts.

And governments figure very prominently in that, because they have been substituting borrowed money for economic activity throughout the pandemic. As a result, government debts have skyrocketed.

On the one hand, this means they will penalize the investors who have floated their loans by paying them back with less-valuable, depreciated dollars. But on the other hand, their cost of borrowing – the interest they pay – will explode, increasing their deficits even further.

A one-percent increase in interest rates doesn’t sound like a lot, but coming from a world where interest rates on government debt were a mere 1% or less, it means a potential doubling or worse in interest costs.

So, “a little inflation” always seems like a good thing. But a little inflation historically leads to a lot of inflation – and that’s never a good thing.

If you want to know what appropriate responses are, reach out to me and ask. There is no one, simple answer, or small set of answers, to “How do I deal with inflation?”

And good luck. I think we are at a critical turning point in economic history. Those who are prepared can prosper, while those who are not will get slaughtered.